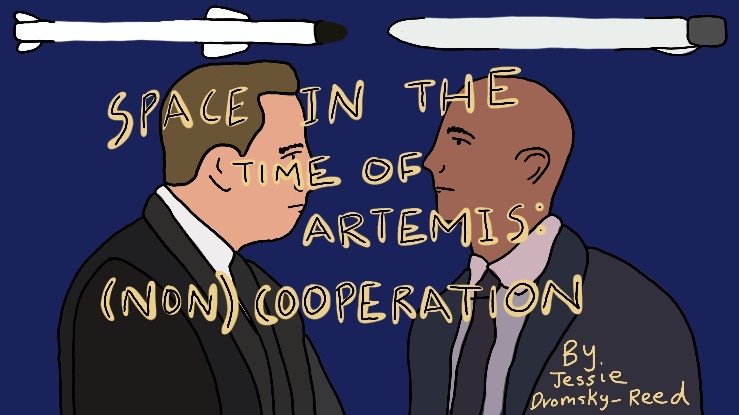

Space in the Time of Artemis:Corporate (non)Cooperation

“Uh…Houston, we’ve had a problem.”

A legal battle and subsequent Twitter war between technology moguls Elon Musk, inventor Tesla and founder of Space Exploration Technologies Corporation (SpaceX), and Jeff Bezos, former CEO of Amazon and founder of the aeronautics company Blue Origin, halted the development and construction of NASA’s newest lunar lander.

NASA’s Artemis Program relies on partnerships between private companies and NASA to design and construct the revolutionary interstellar and lunar infrastructure necessary to turn the Moon into a rest stop for astronauts on their way to Mars.

Since its founding in 1958, NASA has relied on private partnerships to turn science fiction into reality. During the Apollo era, NASA had approximately 400,000 people working to put Neil Armstrong on the Moon. 377,000 of those were private contractors working for companies like North American Aviation who built the Saturn V rocket; the Grumman Corporation who built the Apollo lunar module; IBM who designed the Apollo spacecrafts’ computers; General Motors who created guidance computers and batteries for the lunar modules; and even the International Latex Corporation whose experience molding latex into bras and girdles made them experts in rubber undergarments perfect for spacesuits.

The Apollo Program partnerships were work-for-hire contracts, meaning NASA would do the research and development for a new lunar lander, engine, spacesuit, or freeze-dried meal and present the plans to private companies. These companies would then build the technology to NASA’s specifications.

The Artemis Program partnerships are drastically different. As NASA describes, in order “to achieve [its] goals of expanding capabilities and opportunities in space”, it announced a series of annual competitions (aka very fancy science fairs), the winners of which will get to design and build technology for the Artemis missions. The three largest competitions are the Tipping Point competition, Announcement of Collaboration Opportunity (ACO) Solicitations, and NextSTEP.

These competitions function as follows: NASA announces what it needs for the mission— habitation systems, power and propulsion mechanisms, or a human landing system— private companies submit proposals or prototypes of the new technology that fulfill NASA’s brief, and then NASA selects the best proposal and provides a portion of the remaining funding.

In this regard, NASA functions as a customer of private spaceflight corporations.

NASA stepped into its customer role in 2010 just as the Space Shuttle program was ending, with Elon Musk’s SpaceX successfully completing a test of its Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon spacecraft for NASA.

The Space Shuttle program ended in 2011 due to budget restrictions (in its heyday, the Shuttle would launch about five times a year, and cost roughly $1.5 billion per launch), after which NASA began purchasing seats on the Soyuz rocket owned by Roscosmos, the Russian space agency. As of November 15, 2020, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket and the Crew Dragon spacecraft are the primary vehicles NASA uses to ferry astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS). Its launch from Cape Canaveral, Florida was the first manned space flight to launch from American soil in a decade.

With its longstanding partnership with NASA, it came as no surprise when SpaceX submitted a proposal as part of the NextSTEP competition for companies to design the human landing system (HLS) for the Artemis Program.

It was also not a surprise when Jeff Bezos’ aerospace company Blue Origin submitted a proposal for the same contract in conjunction with three other aerospace companies the New York Times describes as “more traditional and experienced” companies: Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Draper.

Just before the close of the competition in 2019, NASA clarified that it was “expected to make multiple awards to industry to develop and demonstrate a human landing system. The first company to complete its lander will carry astronauts to the surface in 2024, and the second company will land in 2025.” (This timeline has since been pushed back a year so the that the first lunar landing of the Artemis Program will be in 2025.)

On April 16, 2021, NASA announced that just SpaceX had won the $2.89 billion contract.

SpaceX had the green light to begin construction on its HLS Starship, a lunar descent vehicle relying on the company’s new Raptor engines and redesigned Falcon rockets and Dragon vehicle. The Starship will have a cabin for the descending astronauts and two airlocks for moonwalks.

Ten days later, Bezos and Blue Origin filed a protest against the award with the Government Accountability Office (GAO), beginning lengthy legal and twitter battles between the two companies and their owners, and halting all HLS development and production.

Blue Origin Chief Executive Bob Smith explained the protest to the New York Times, claiming that “NASA’s decision was based on flawed evaluations of bids—misjudging the advantages of Blue Origin’s proposal and downplaying technical challenges in SpaceX’s.” The New York Times also reported that Smith thought “NASA had placed a bigger emphasis on bottom-line cost than it said it would”; it’s hard to restrict our imaginations by our budgets.

And while Blue Origin’s bid of $6 billion was more than double SpaceX’s, Smith claims that NASA went back to SpaceX to negotiate the price further without giving Blue Origin the opportunity to re-evaluate or negotiate its price. Smith is quoted saying, “We didn’t get a chance to revise and that’s fundamentally unfair.”

Elon Musk’s, and subsequently SpaceX’s, only response to the protest was a tweet at the New York Times reporter Kenneth Chang, author of the article referenced above, mocking the fact that Blue Origin had yet to successfully launch a rocket into low Earth orbit:

On July 30, 2021, the GAO denied Blue Origin’s bid protest, meaning that SpaceX had won the contract, could keep the money, and move forward with HLS Starship’s construction. However, Blue Origin resisted the GAO’s ruling and filed a complaint with the U.S. Court of Federal Claims against NASA on August 16, 2021, again halting HLS construction.

In the lead up to the Blue Origin’s filing in federal court, the company waged a social media campaign against SpaceX’s HLS Starship through a series of infographics detailing the “immense complexity and heightened risk” Starship poses to the Artemis Program and its astronauts. CNBC Space Report Michael Sheetz tweeted one of these infographics, earning a response from Elon Musk:

Only when the U.S. Court of Federal Claims announced on November 4, 2021 that it would side with the GAO and NASA, did Bezos concede the contract. Via Twitter, Bezos explained that this was “not the decision we [Blue Origin] wanted, but we respect the court’s judgement.”

Elon Musk responded on behalf of SpaceX—

—and finally began constructing the Starship.

It is very concerning…

that a legal argument and subsequent Twitter battle between two men can shut down a multi-billion dollar, U.S.-led, international program to return humanity to the Moon. And it calls into question who really controls access to space.

In the past, the answer would have been NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), Roscosmos, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), or any number of other agencies regulated by governments who had signed on to the Outer Space Treaty, a treaty whose primary goal is to maintain peace in space. Today, the answer seems to be billionaires whose celestial ambitions are fueled by vanity and money.

Elon Musk has begun monetizing space by selling seats on his Ispiration4 rocket for undisclosed sums of money. All four seats on the first ever, multi-day trip to space without professional astronauts were purchased by Jared Isaacman, the founder of Draken International, a private air force provider, and Shift4 Payments, a payment processor. Al Jazeera describes him as a “billionaire businessman”.

Jeff Bezos followed close behind Musk with frequent suborbital space flights for high profile passengers like William Shatner (the original Captain Kirk), Michael Strahan (former NFL player for the New York Giants and TV celebrity), Laura Shepard Churchley (daughter of Alan Shepard, the first American in space), and lesser known but equally wealthy CEOs, investors, and their families.

Now, while I relish the prospect of being able to fulfill a childhood dream of traveling to space one day, I highly doubt I will ever make enough money to afford a ticket on board Musk’s or Bezos’s space crafts. These space tourism endeavors are created by the top 1%, for the top 1%, in the name of enhancing all of humanity (the other 99%).

Additionally, what could happen to a space program relying so heavily on billionaires like Musk and Bezos if Congress decides, for example, to pass regulations restricting the use of electric cars that Musk does not like (Musk made his billions as the founder of Telsa, an electric car company)? In an effort to get the government to swing this hypothetical legislation in his favor, could Musk hold the space program hostage and refuse to construct any further rockets or spacecrafts? In this hypothetical, perhaps even dystopian, situation, the U.S. government would become subservient to Musk’s ambitions.

Do not mistake my criticism of the current state of celestial affairs for cynicism. I am just as enamored with the prospect of seeing the world progress in a direction that may allow my descendants to see ships that resemble the Starship Enterprise or the Millennium Falcon as anyone else. But, studying the world today, I am worried that that’s all my descendants will be able to do: see the ships. As the top one percent further expands the wealth gap through space flight, it takes the possibility of new knowledge and exploration away from the rest of humanity.

We are standing on the precipice of a new era of exploration. But it will not look like any previous generations’ exploration, with people from all walks of life escaping persecution or seeking new life and wealth in a new land. Quite possibly, it will be rockets filled with those who have already acquired vast wealth seeking shelter on the Moon or Mars, and leaving the rest of us behind.

**This is the second part of a two part series**

Read the first: http://www.wearegenz.org/portfolio/space-in-the-time-of-artemis-international-cooperation/